The perfectly flat road, naked sky and vast farmland met at an infinite point on the horizon. Even the mighty Sierra Nevada mountains to the east were hidden in that place where the baby blue sky faded into a dirty white translucent vapor before abruptly drawing a line at the ground. This is the middle of nowhere, somewhere southeast of Chowchilla, California.

Driving north, a row of trees to the west obstructed the view of the towering lights, nondescript tan concrete buildings and hostile fences leading to the entrance of the Central California Women’s Facility. However, the event on this cool, late fall day is taking place at the men’s facility at the next crossroad to the north.

Leaving cell phones behind, Fresno State students and faculty are checked in and moved into a small holding area with high fences topped with copious amounts of razor wire.

“Don’t forget they’re inmates,” a guard says before buzzing the door into the holding area.

As the group was escorted to the visitor center, they could again see that view of vast emptiness. A somber reminder that even when one exits the fences, there is a long way to go. The visiting center gave off hard elementary school cafeteria vibes, but rather than a kitchen, there were visitation booths with two-way telephones and thick glass.

On Nov. 13, 2023, the tables were folded and staked to the side. In their place, chairs were set up for an audience to witness the first-ever debate between incarcerated college students and a collegiate debate team in California.

“That was the first time I ever walked into a prison,” said Rhiannon Genilla, a Fresno State student, during the first debate. “I didn’t really know what to expect. I just knew I really loved debate. Coach Doug had been teaching them throughout the semester and had awesome things to say. So I wasn’t really scared, but I didn’t know how to feel about all the big fences, barbed wire and the correctional officers.”

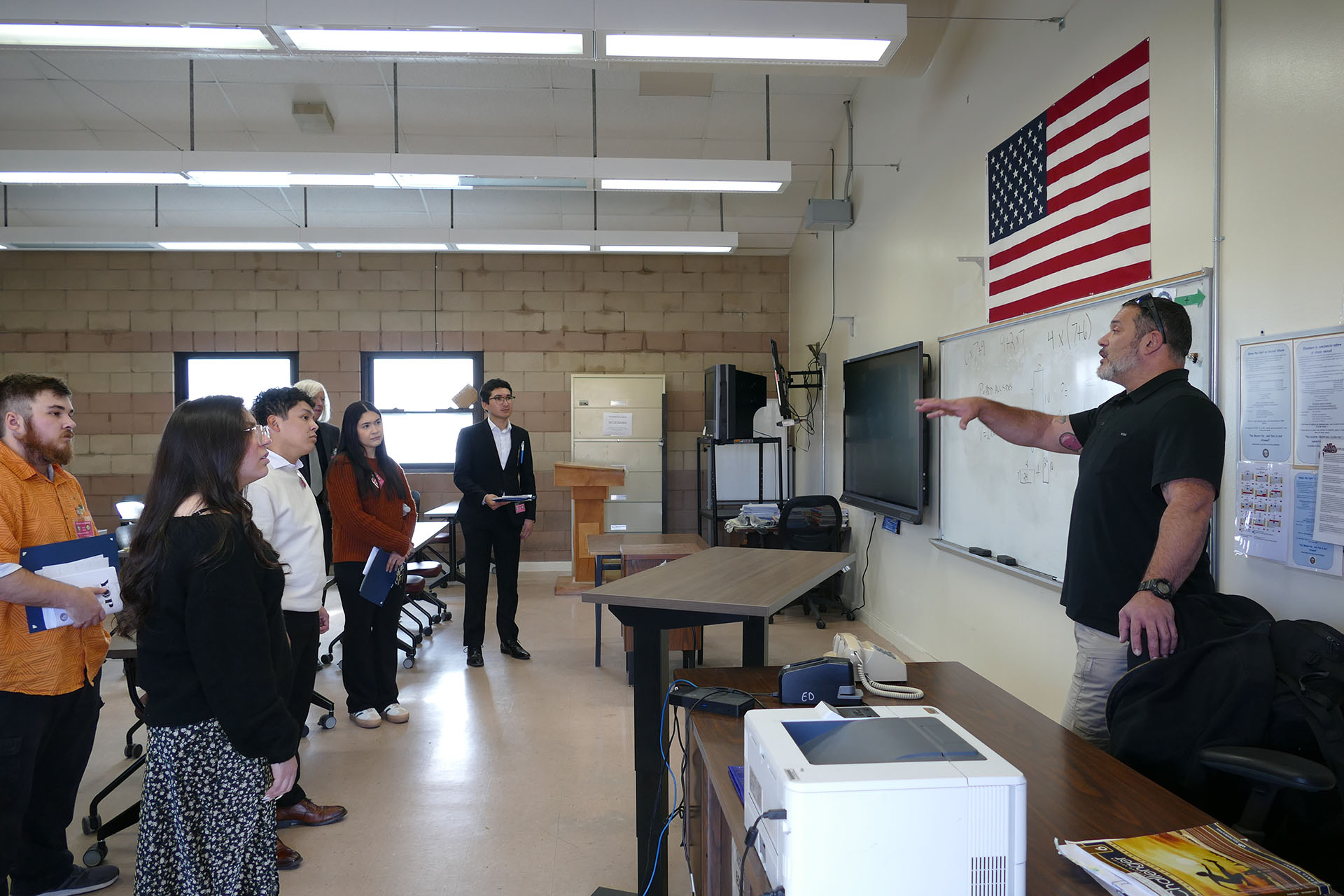

Beyond the drab setting, the debate was fairly standard. Students on both sides took to the microphone to present their sides while the other team vigorously took notes. The prison’s debate team included incarcerated college students enrolled through Fresno State or Merced College. The 12 Fresno State Barking Bulldog debate team students traveled to the prison for the event.

According to the California Department of Corrections, debaters were selected to join the debate team based on their grades, attitudes and disciplinary records.

Now a graduate student in the Department of Communication at Fresno State, Genilla drives to the Central Valley Women’s Facility every two weeks to coach their new debate team.

“I really do believe that God has led me on my path,” said Genilla. “Jesus says to visit the prisoner, and I didn’t know that I was going to be on my path. And it’s been amazing.”

As of March 2025, there have been three live debate events at the men’s prison and one at the women’s facility. While the incarcerated students are pursuing their bachelor’s degrees, the debate program is an extracurricular activity.

Degrees of Change and The California Model

In 2014, Chapter 695 was signed into law, allowing California’s community colleges to receive full state funding to offer credit courses inside state correctional institutions. This allowed Merced College and most other California community colleges to offer in-person courses and degree programs within prison walls.

Project Rebound expanded to Fresno State in 2016, and Dr. Emma Hughes, Professor of Criminology in the College of Social Sciences, was named the founding director. Project Rebound was initially founded at San Francisco State University in 1967 by the late Dr. John Irwin, a formerly incarcerated person who turned his life around through education. Project Rebound is now at 19 CSU campuses.

A shining example of Project Rebound’s success is 2022 Fresno State President’s Medalist Steven Hensley.

“I was starving on a park bench after being released from prison. I didn’t know how to navigate the free world,” Hensley said in a 2022 interview.

He recalled seeing a Fresno State Project Rebound flyer in Avenal State Prison. He found his way from that park bench to Fresno and was able to enroll as a double major in philosophy and political science at Fresno State. Hensley is currently a Juris Doctor candidate at U.C. Berkeley School of Law.

After a short pilot program, in 2022, Fresno State announced the Degrees of Change program, which offered a B.A. from the College of Social Sciences through the Division of Continuing and Global Education. While Project Rebound worked with formerly incarcerated students, Degrees of Change took it further and moved the classroom inside the correctional institutions’ walls. Dr. Emma Hughes was again key in starting the program after the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation contacted her and asked if Fresno State would be interested in offering a bachelor’s degree inside Valley State Prison and the Central California Women’s Facility.

The California Model was announced by Governor Gavin Newsom in 2023. The pilot program was first rolled out to pilot locations, including Valley State Prison and the Central California Women’s Facility, and is inspired by the Nordic correctional systems. The model is built on four pillars of dynamic security, peer mentorship, normalization and becoming trauma-informed organizations. Its focus is on positive interactions between incarcerated people and prison staff, reducing recidivism through scholastic and vocational education programs and recognizing and treating the role trauma plays. Correctional staff across the state are expected to complete their initial training in the new techniques by the end of 2025.

Don’t forget…

“I’m a professor from Fresno State. I’m teaching a class,” Brenna Womer, Department of English, recalled saying to the guard as she entered the Central California Women’s Facility to teach English 174, popular fiction, for the first time.

“Hey, don’t forget they’re inmates,” the guard said as they waved her through the door.

The comment shook Womer.

“The way that that guard felt the need to assert to me, like, ‘Hey, they’re not students first, don’t forget.’ And realizing that level of dehumanization that they face on a daily basis.”

Incarcerated students and instructors said the simple act of calling incarcerated students by their first names becomes a revelation. They are more than a number. In the classroom, they are independent and free-thinking. They are human.

“I got into it because I find our prison system and our judicial system really problematic. Being part of the education is a way to be part of the positive change and the good. But then you’re still there, you’re still in it. And you just never forget how much they’re punished,” said Dr. Jesse Scaccia, associate professor of journalism. “I’ve seen students go from ready to be done with life to believing themselves again and really turning their narrative around. So, if I ever needed to have testimonials or faith renewed in education, this has totally done it because you really can learn and write your way to a new self.”

Through the literature courses, incarcerated students see themselves in novel characters and find personal connections in their suffering and redemption.

“Some of the stories that they’re putting on the page already are some of the most tragic and traumatic things that I can imagine a person going through. That’s what they’re seeing and feeling when they’re reading literature and relating to characters. And, it’s something that they carry with them all the time,” said Womer.

Through the debate team, incarcerated students learn to articulate their points respectfully and intentionally, beyond an emotional response.

“I had a student tell me how much he struggled with anger issues, and now he has skills to turn that anger into something that can benefit him rather than just continue to self-harm something productive,” said Genilla.

Through writing, incarcerated students can process trauma through self-reflection and narrative.

“Teaching personal narrative and memoir, I’ve read their stories. It’s so different to hear about somebody’s life crime on page 120 of their life story than it is to see the headline of the ‘life of crime,’” said Scaccia. “Almost to a person, they have been abused. They have suffered from addicted parents. They have suffered through a kind of poverty that is rare in our society. They went from being victims and then so often drawn into gangs by poverty and by lack of that family structure. And then they’re 17, and they commit a life crime, and we decide they’re just this horrible person. When, if they had been born in a different scenario, or if I had been born to that one, the roles would likely have been reversed.”

Freedom

To say students in the program are eager is an understatement. Instructors say they are incredibly engaged and come to class with deep insights. This is without access to internet browsers, AI tools or other outside materials that traditional students have access to.

“They’re hungry for it,” said Womer. “On day one, they were like, ‘How much extra credit can we have?’”

The craving runs deeper than passing time. All of the students, according to Scaccia, have full-time jobs. They work from 7 a.m. to 3 p.m. and then attend class until 9 p.m.

Their primary motivation?

“Freedom,” said Scaccia. “This gets them time off. From what we’ve seen, to the parole board, it means a lot when they get this bachelor’s degree. It seems to really be a help. It helps them get out.”

While the bachelor’s degree looks great on paper to the parole board, the humanities courses have taught them to reflect on their past and write their own story for their future.

Womer explained, “I’ve realized we’re helping them craft narrative. We’re helping them strengthen their communication and writing skills. And when they are going up for parole, they submit narratives. They have to write, they have to plead their cases, they have to be able to express themselves and narrativize their experiences.”

On Oct. 18, 2024, nearly two dozen inmates walked in the first-ever commencement for incarcerated individuals at Valley State Prison, earning bachelor’s degrees through Fresno State’s Degrees of Change program.

“The Degrees of Change program embodies the ethos of Fresno State,” Fresno State President Saúl Jiménez-Sandoval said during his commencement address. “Higher education is more than a privilege for the few — it is a journey of self-discovery and reflection about one’s self, one’s responsibility to others and one’s ability to contribute, when given a second chance, to society’s betterment; it is a powerful force for all, regardless of circumstance.”

On March 11, 2025, 17 students walked in the first Fresno State graduation ceremony inside the Central California Women’s Facility. Three additional students earned their degrees but had already been released and were unable to attend the ceremony. One student was recognized posthumously with a certificate of achievement.

There are currently several students who started their journey in higher education while incarcerated who have been released and are currently completing their degree on campus through Project Rebound.

Congratulations, Jason Lint, graduate.

LikeLike